The Bangladesh prime minister Sheikh Hasina is on a four-day official visit to India, starting today. Thus, now is a good time to ask these tough questions: why is India’s neighbourhood engagement important? Is there a need to revaluate India’s benevolent policy towards small states in its neighbourhood? And finally, should India oppose the growing Chinese presence in the Indian subcontinent?[For an analytical definition of the term small states, refer to this paper.]

Kathmandu, SAARC Summit 2014 [Image courtesy: Flickr, User: anantablamichhane, Licence: CC BY 2.0]

In reality, a lot of India’s “benevolence” is motivated by old, misguided notions like India’s Monroe Doctrine—an idea that perceives small, sovereign states in vicinity as “India’s own backyard”. Such a view underplays the agency of these states as independent actors and is thus obsessed with India’s own presence in these countries. This view is outdated. These false notions impede a realist assessment of India’s neighbourhood policy.

Now, returning to the big question: if the most fundamental aim of Indian foreign policy is to ensure peace and prosperity for all Indians, in what ways can small states in the neighbourhood achieve this aim? I contend that the role played by these small states has changed, and substantially so. Until about a decade back, India’s challenger in the subcontinent was Pakistan, China was barely interested. In those days, a benevolent small state policy — one that went beyond strict reciprocity — served India well. It was necessary to ensure that small states did not turn a blind eye or support Pakistan’s terrorist agenda on their respective territories. Even without the Pakistan angle, cooperation with small states on the eastern front was important for eliminating terrorists operating along India’s north-eastern borders.

Times have changed since then. Tolerating Violent Non-State Actors (VNSA) is no longer an option even for small states. The lesson that “Snakes in your own backyard won’t bite only neighbours” has now been internalised by small states. Pakistan’s own internal struggles with terrorism serve as a testimony to the long-term negative consequences of such a policy. So, small states today are more than willing to seek help from bigger neighbours in eliminating VNSAs. Given this change, India no longer needs to commit all-weather support to its neighbours sans symmetric reciprocity.

Next, beyond the security domain, there is very little that small states in India’s neighbourhood can do in India’s pursuit of prosperity for its citizens in the immediate future. As we enter a world economy that is getting increasingly protectionist in nature, international trade will become increasingly difficult. Fortunately, India’s big, relatively young, and diverse population means that greater domestic consumption alone can help us maintain high economic growth for the next 10 years or so. Barring Bangladesh, no other Indian neighbour has economic prowess that India cannot substitute domestically. So, in the short run, the economic benefits accruing from small states in the neighbourhood will continue to be marginal.

Now, to the most important question: if India takes away its small states focus, won’t the Chinese influence increase? My counter is: can India resist the growing Chinese presence in its neighbourhood with manageable costs? After all, it is perfectly natural that small states will play India against the bigger economy, China. Shiv Shankar Menon in an interview to The Wiredescribes the relationship between China and small states in India’s neighbourhood best, when he says:

So that’s a relationship there and I think we should get used to the idea that all our smaller neighbours, if they see India-China rivalry, will find it useful to deal with us in order to get things from the Chinese and deal with the Chinese in order to get things from us. I mean, I would do it if I were a smaller neighbour and I would maximize my gains. So I think we should be ready for this. I don’t think we should aim for exclusivity or some zone where people only deal with us… Why would they put themselves in that position? They’re sovereign states, independent.

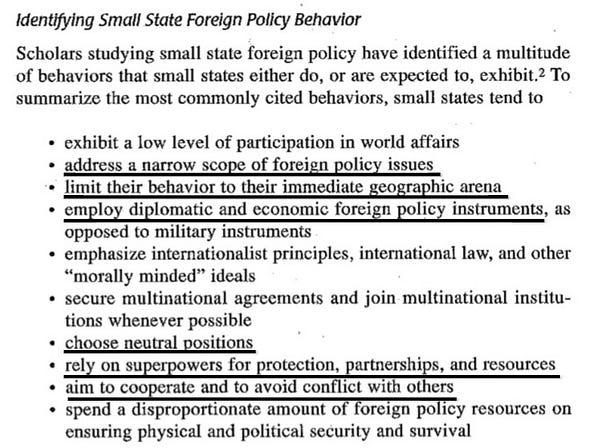

Jeanne Hey’s articulation of small state foreign policy behaviour in the adjoining figure also suggests that the behaviour of small states in the Indian subcontinent is archetypical.

In fact, it’s better for India if China gets involved in the subcontinent so that India does not have to bear the cross of the “domineering big brother”— a convenient excuse deployed by small states. Given China’s unenviable performance in other small states, it is likely to establish itself as a primary object of hate in these coutries very soon.

This is not an argument to suggest that India should let China have a free run in the subcontinent. The only lesson is that India should not be obsessed with Chinese involvement in the subcontinent. India must however, do enough to be the second-best option for small states.

Thus, India needs to stop worrying about China’s presence in its neighbourhood and instead focus on domestic economic concerns. May be, it’s India’s time to “lie low” in its neighbourhood for a few years.

A discussion with Nitin Pai sparked some of these thoughts.

No comments:

Post a Comment